Progress is almost certainly agreed to be necessary but progress does not mean that what is old is no good or useless anymore unless that’s an aspect inherent to the design. We need to recognize the waste that progress can sometimes bring and try to minimize it at every turn.

I have worked with a number of product managers of digital and physical products over the years and one of the topics that doesn’t really come up is the question of obsolescence (planned or otherwise).

Planned obsolescence conceptually emerged almost a century ago with Bernard London’s pamphlet Ending the Depression Through Planned Obsolescence. His plan would have the government impose a legal obsolescence on personal-use items, to stimulate and perpetuate purchasing.

The concept was popularized in the 1950s by American industrial designer Clifford Brooks Stevens who used the term as the title of his talk at an advertising conference in Minneapolis in 1954.

By his definition, planned obsolescence was “Instilling in the buyer the desire to own something a little newer, a little better, a little sooner than is necessary.” Stevens saw this as a cornerstone to product evolution.

What is often recognized, is the importance of customer retention, optimality in the customer experience, product reliability, fitness for purpose and so on. How often does product durability get factored in? It seems the answer to that question depends heavily on the industry segment and the perceptions that exist around how long is a reasonable time before the style, performance and capabilities of the product wane.

There’s an industry segment known as FMCG, Fast Moving Consumer Goods, it’s a popular acronym and taught widely at business school but what does it really mean in our modern world? A Wikipedia definition will frame it as “also known as consumer packaged goods (CPG)… products that are sold quickly and at a relatively low cost. Examples include non-durable household goods such as packaged foods, beverages, toiletries, candies, cosmetics, over-the-counter drugs, dry goods, and other consumables.” So, we get it, they’re stuff we consume regularly and don’t expect to have sitting on the shelf or in the cupboard for a long time.

There’s this other class of goods known as “consumer durables”, another business school term, the name is a clue to the expectation around these goods; it is something that should last. Again Wikipedia frames it nicely as “a category of consumer goods that do not wear out quickly, and therefore do not have to be purchased frequently. They are a part of core retail sales data and are known as “durable goods” because they tend to last for at least three years.” But there’s a problem here, who decided that three years was the minimum life span for these things?

It seem the question of product durability of products, particularly physical ones, has been a concern for a very long time, so much so, that various nations have invested in studies and programs to try to drive product durability standards and ensure that manufacturers product products that last.

In some studies it has been suggested that more than three quarters of consumers believes that products do not last as long now as in the past. The shape of consumer sentiment is clearly negative. It is also clear that in our world of finite resources and the growing waste problem that there are persuasive arguments that favour extended life expectancy out of products. This is driven not only by the direct savings resulting from less frequent replacement of products to experiencing greater reliability and fewer repair costs. Extending product life ultimately is of benefit to society as a whole. Save material, save energy and save the environment.

Manufacturers will cite that there are problems and limitations with this approach, for example, that increased life for certain products can be purchased only through significantly increased costs of production. Using more costly materials, metal instead of plastic for example. They would also say that more expensive more energy intensive manufacturing methods would be required. Again, the metals vs plastics argument. If longer lasting products are more expensive, then the direct savings to consumers may likely never be possible.

How we calculate the cost

In our minds, if we buy something today with a forecasted life of say 5 years then we work out that the cost is roughly a fifth of the total cost every year. The higher the price and the lower the durability, naturally, the higher the holding cost. This is effectively how we see the discount or lack of discount in our minds. Buying a high end mobile phone for $1000 today and expecting it to last for 5 years means $200 dollars a year. If you tell me that it will only last two years then the $500 a year might be a price point that discourages me.

Obsolescence is fundamental to the experience of modernity, not simply one dimension of an economic system.

Cultures of Obsolescence: History, Materiality, and the Digital Age – B. Tischleder, S. Wasserman

The main argument against durability, as presented by manufacturers and product designers and managers is that if a products lasts longer then the turnover rate of that product will be slow and this will inhibit the ability to fund new product design and related innovations because the existing products will be what they are and capital will be tied up in the inventory and the old technology. This is also one of the catalysts behind just in time (JIT) manufacture and other innovations around stock minimization.

With the burgeoning focus on more efficient transportation like E/Vs and water and energy efficient appliances with elevated levels of safety you could say that we should not be trying to perpetuate existing products in their current form but should always be looking forward and improving, and besides, if you ‘re not continuously producing then there is retarded economic growth in industry and the potential for unemployment or at the very least under-employment.

So, we’ll take longer product life as long as we don’t have to suffer unacceptable side effects. Society will opt for more durability in products if the negative impact is reasonably benign.

Planning for durability

Product managers and designers should consider an approach to product durability that carries at least two important aspects

- identify if a longer product life is a desirable goal

- identify product life durability strategies that will have minimal adverse effects

From a design and manufacture standpoint this means focusing on just how much value is added through the raw materials to finished product production process, the value of the materials and energy involved in the production; the effects on the environment; and the actual potential impact of increased life.

Products that have high level of value-added either through labor, energy or materials would be the obvious ones that should have the greatest durability because of the value invested in the product. Extending product life complements

recycling as a conservation strategy.

The high tech industry has only recently started to point out the social and scarcity costs of some of the rare metals materials associated with production costs and while there is some acknowledgment of depleted energy resources used in production, these clearly don’t appear to be strong drivers to slow the release of increasingly faster, newer and feature-full new high tech products.

Additional burdens like toxic waste or aspects inherent to the product that need proper or specialized disposal might also be considered a part of this.

I guess the point of all this is to double-down on recognizing the overall sensitivity that we need to have, as consumers, as technologists and as technology advocates for the most appropriate orientation to product conception, design and production.

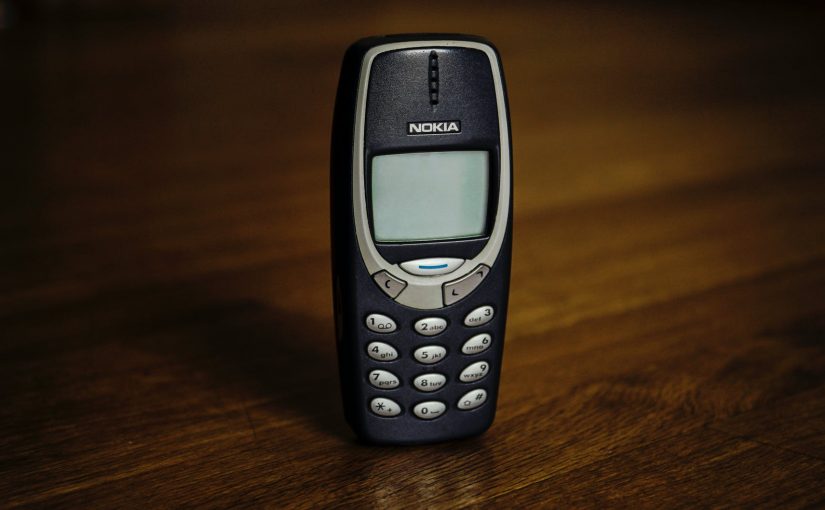

As consumers we want the latest, most powerful camera phone, for example. It won’t change the experiences we have already had or the moments in life already captured but it does have other costs. The existing camera phone we have, may have its limitations in contrast to the new ones, but are they really that materially significant? Perhaps not. More importantly, if I have a social conscience and I want to keep using my existing phone until it basically completely stops working, fails to hold a charge, gets lost or damaged irreparably, surely that is the point at which I should replace it?

I shouldn’t have to replace it because the piece of software or app that I use almost everyday, decides it is time to update itself and then declares that it will not work on the version of the operating system that my phone has – that, to my mind, is unacceptable and tantamount to planned obsolescence.

This is also myopic thinking on the part of the developers, the designers, the architects and the product managers responsible for those lines of digital products that they’ve decided should now run exclusively on new hardware. Sure, backwards compatibility is hard but failing to consider the broader implications, particularly with software and digital products, of the existing customers is bad product management. Even if you back your position up with empirical data, be sure that you’re looking at the whole ecosystem before you decide to brick the experience.