I have observed a healthy and somewhat heated debate on the topic of matching up data records and the kinds of matching that one can have between data. This prodded me to do a little more research and investigation into the topic and ultimately led me to reduce the topic to a few words on the different types of matching and the approaches that one might consider.

I started with a company whose resources I have used in the past, namely Add-In Express for Microsoft Excel and this then led me to an article by Svetlana Cheusheva from ablebits.com who nicely broke down a number of direct comparisons and matching techniques that you might use with Excel around vlookups and index based matching.

Excel is a pretty ubiquitous tool used for matching data and commonly used for the small dataset comparison activity.

It is important to note that in any data management activity, one of the missions in pursuit of data qulity has to be the reduction or elimination of duplicates, and in particular duplicates that could potentially mess up any downstream activities that you might have in mind, like record-mastery.

Comparing Differences

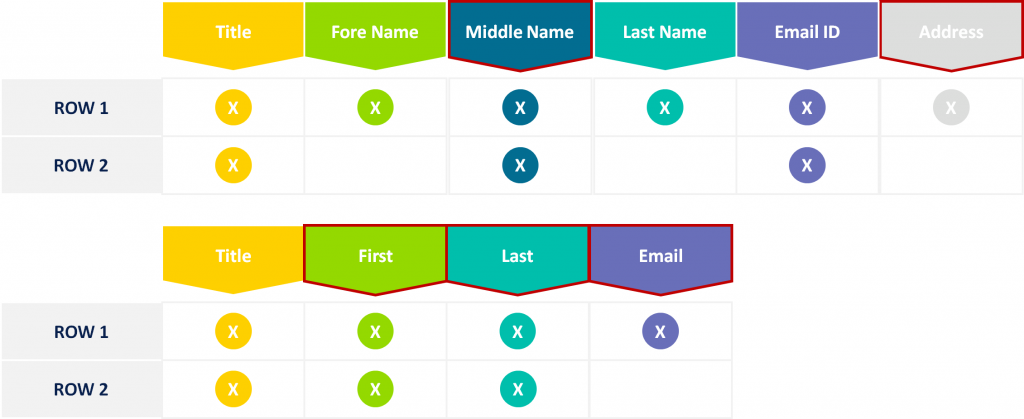

There are two primary considerations when comparing two data sets. The first is, are the two data sets ostensibly the same? By this I mean, do they have the same rows and columns? This applies not just to Excel data, but in fact any sets of data. It is an important baseline comparison when porting or moving data between systems.

In my mind, this is a file comparison that goes beyond the bits and bytes of the file, such as date and time of creation and the size of the file. With smaller files, this can be done with a simple eyeballing.

With larger files, you need the means to do the comparison with technology. The intent is to determine whether the schema (columns) may have changed and to determine if the actual contents are different.

There are two distinct tasks to undertake in dataset with dataset comparison but the first of these is important for comparing schemas also.

Schema comparison

You’ll need to do this in order to ensure that you don’t have the same schema unnecessarily defined more than once, and more importantly you will need this for integration or use case mapping.

If your target system is precious about schema column sequence that will be an important aspect, if it is a concern about column labels then that will be another.

This assumes that you have a master and you are trying to determine if subsequent schemas actually match up with your master.

This is a relatively fast and economical way of determining whether the shape of two datasets is likely to fit.

Dataset content comparison

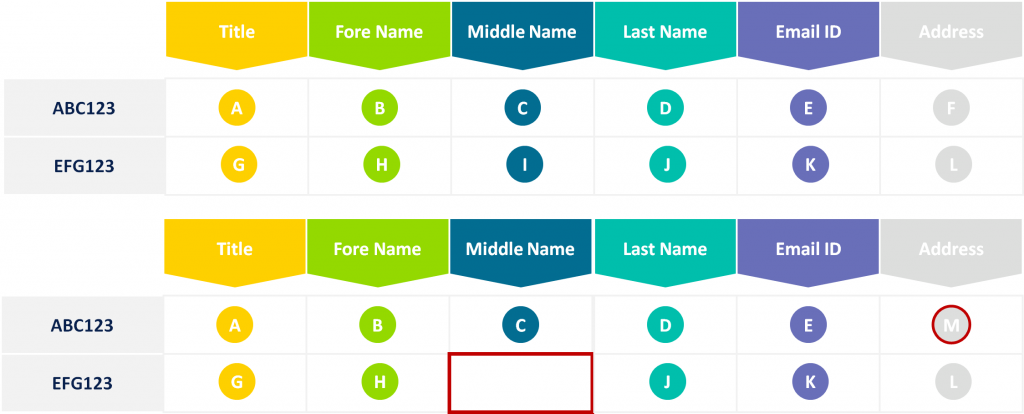

Here you want to determine whether content in the two datasets is the same, where the schema has no discernible differences but where the values may have changed

You might need to do this for delta processing changes between two datasets and often an easy way to solve for this is to generated a hash of the contents of each row and compare the data that way.

Hashing the content is the fastest and most economical way to do this.

Cell by cell comparison between two grids

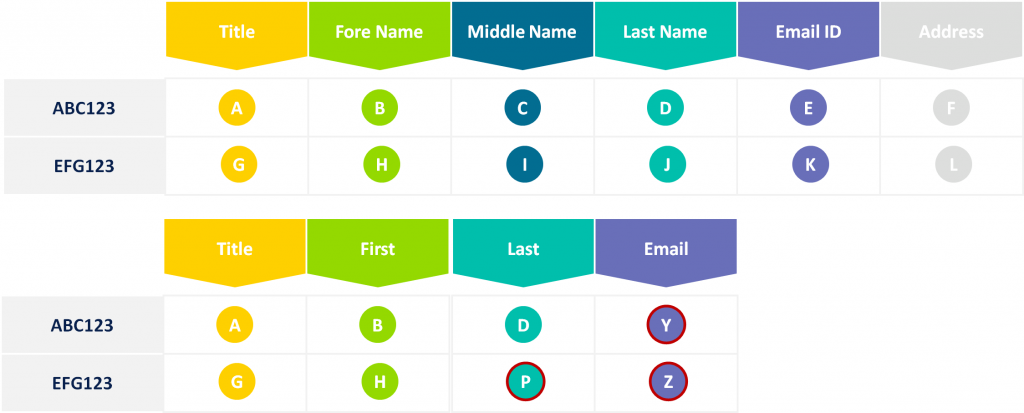

This is the most expensive approach to dataset comparison, here you may have schema differences but as long as you appropriately map the schema identifiers the next challenge will be to work out with the data that you have, which content is wrong/right/missing.

The way you might do these comparisons in Excel is nicely described in one of the article by Svetlana, but for other technologies, ironically, this might not be as straightforward.

This leads me to the discussion or consideration of the use cases or use cases that one might have in mind.

Use Cases

In the data management realm there are principally two kinds of data. Master data and transactional data. There may be others, but those, for the most part, are beyond the consideration of what I have in mind. For example, you might call out various kinds of metadata, at which point I might ask, for what purpose?

Continuing along this line of thinking here, when we consider master and transactional data there are principally only a handful of reasons why I might be doing comparisons between datasets and considering differences.

In the case of masterdata, I might, as previously suggested, be moving data between systems and I might be very keen to make sure that what I started with, is what I end up with in the target environment.

A second consideration with master data is the desire to determine what has been added or changed in a given file since the last time that I staged, cached or loaded that master data.

When I have very large data sets of say business partner data (vendor, employee or customer), I might want to ensure that the new records that are coming from another file, have not damaged or contaminated my original file’s contents in a deleterious way.

This would include incorrectly nulling out values, the creation of duplicate records etc. The techniques for this may vary wildly. Some columns may be appropriately classified as nullable, some columns should perhaps only have values from a defined list or range, the contents of others perhaps should be presented in a particular format.

In such instances, I might use a variety of tools to perform value, range, and format checks to ensure that the data is proper and consistent. For some columns of data, particularly descriptive strings, I need to consider comparisons for case, field length and fuzzy matching.

By fuzzy matching, I am referring to techniques that determine that the contents of the strings are close enough that they might, in fact, be duplicates. For transactional processing the issues are largely similar but with an intent to either identify patterns or avoid duplicates because they ruin analytics.

The intent with transactional matching is perhaps more focused on cleaning up data for analysis. With master data, the intent is largely to accelerate or straighten out the master record selection choices for transactional processing activities – there may also be an analytics and reporting interest here too, though.

Delta Processing

In some areas, if the schema is the same between the two files and one is simply looking at differences since the last check of the contents, one is effectively looking at a delta processing based approach to comparison. While on face value this looks like cross-file matching, my view is that it is not. It is in fact simply delta file processing.

You’re looking for the changes in a nominated “best set” of records, relative to a list of the same or similar records, and looking for the deltas or changes.

Change data Capture (CDC) technologies often are used to generate or create these delta files so as to reduce the dependency on reprocessing the same original or large file dataset.

Records identified from the delta file as duplicates or close matches may then be merged or discarded. Completely new or apparently new or sufficiently different records are then appended to the earliest of the data sets to converge on a master.

Persistent Keying

There are a number of technologies on the market for golden nominal creation. This is also considered master data management or persisted ID or persisted keying. In most instances, I take the position that you have to create or nominate a target system as your golden record or golden nominal repository. Your system of record, if you choose it to be.

Depending on the data that you are working with and the industry that you work in, these could vary wildly from an Experian ExPin, a D&B identifier or to something as fundamental as a National Insurance, National Identity or Social Security Number.

In the D&B world, if you have a set of partner data and you are trying to determine if there are any duplicates within that data set, you would usually run some initial cleansing to remove special characters and noise from the data.

Where address data is found, you typically correct the address to a proper address against a Postal Addresses File (PAF) and there are a number of vendors in the market that can support you in doing this.

This address cleansing itself is a type of matching process that uses sophisticated algorithms beyond merely street, town and postcode. The best tools standardize the address, or decompose it into its critical pieces and then uses these all in combination to realign with a proper PAF address.

The standardization process also applies to names and other data attributes to help with ‘matching’.

Once you have run and corrected your data or aligned it with what is needed for the best possible candidacy assignment. In the case of D&B, you are looking within a D&B repository for records in your own dataset that are identified as potential matches.

A well-considered API or matching approach is one that does not rely exclusively on exact matches, but also looks at fuzzy matches. The results are typically qualified according to the closeness of the matches. If exact matches are found, the identifier would typically be appended so that you can again make a decision to blend or discard the records you have or to make a determination that these are, in fact, entirely new records, never seen before